Is February really the optimal time for implementing our New Year’s resolutions? New self-care articles sell us a second chance at reassessing our goals and rebuilding habits, all without the initial pressures of starting out the year strong. But what the self-help guides fail to address is the idealism at the root of all resolutions. It’s possible that the forgiving February we have fashioned is but a reflection of our need to romanticize instead of realize.

This paradigm of the December resolution, then the January relapse, followed by the February overcompensation, hints at our generation’s perpetual chase toward an ideal state of productivity. Yet what is also unique to us is our approach—we want it to be as fast-paced as possible. We dart from shortcut to shortcut on our goal-setting paths, from bullet-journaling TikToks to shopping lists to personal finance videos. The sheer volume of advice matters more to us than how realistically we expect to implement it—and besides, if someone else films a seven-day gym vlog, we feel, even for a fleeting moment, as if we could do it too. Social media enables us to brainstorm resolutions formed by the collective instead of by our own, slower introspection—resolutions that inspire the idea of new beginnings but fall short in practice. It’s easier to throw ideas around in a conversation than it is to apply those ideas to ourselves. And this is why we so desperately want a do-over month—we’ve juggled more than we can realistically handle throughout the first round, but we’re confident that we can bounce back.

Still, Forbes points out that only 9% of adults manage to do so, and the majority quit by mid-February. It offers the simple remedy of making one’s goals more pointed—for example, instead of merely wanting to change management styles at work, decide on how you’re going to do so, and add a time limit. Of course, the majority of our goals happen to be success-oriented, with a Northwestern Mutual Study ranking financial confidence being Gen Z’s top resolution interests. Older adults, however, were found to primarily focus on personal wellness and nurturing relationships. This makes intuitive sense. The younger you are, the more you are likely to work on building stamina, that is, from physical exercise to schoolwork to job hunting. And this pursuit is, in many ways, dependent on extrinsic motivation. It’s easier to set workout goals with a friend, and it’s easier to network your way into a career. But, clearly, our goals tend to shift to the intrinsic as we age. Family time and social engagements matter to us because we realize our time is limited, and it forces us to slow down.

Even if our goals are natural for where we are in our lives, why then are they so difficult to keep? Perhaps the issue lies not in our overcommitment, but in the very nature of the resolutions themselves. If our early, extrinsic resolutions have little use for our lives, it may be time to change them. And if we find it so easy to give up on these little self-promises, they may not have mattered to us very much in the first place. Our formative years are the most exhilarating, and far too short to spend regretting our inability to live up to ideals we can’t resonate with. We shouldn’t wait for the very last stretch of our lives to consider the intrinsic. To cultivate the irreplaceable. Relationships with other human beings—not the parasocial kind, but the kind that is rooted in friends and family—begin from small steps, from phone calls and shared meals. They create snapshots of memory that don’t check any of the boxes on your to-do list, but still linger as you watch the ball drop in Times Square. In light of focusing on the simple, include the people who make you whole somewhere on your vision board. Perhaps, then, you won’t need a do-over month.

—

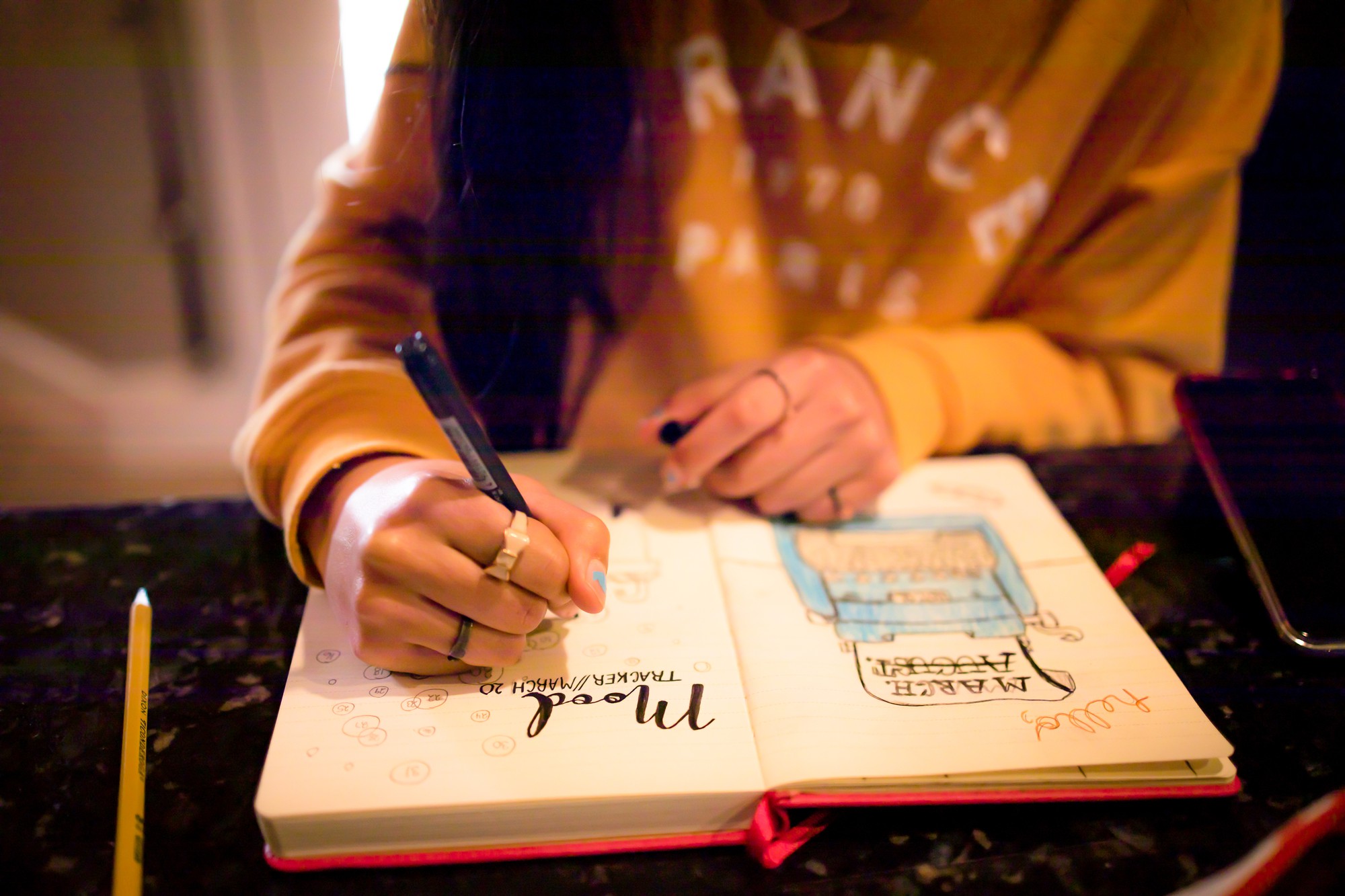

Featured image via Adobe Stock